Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

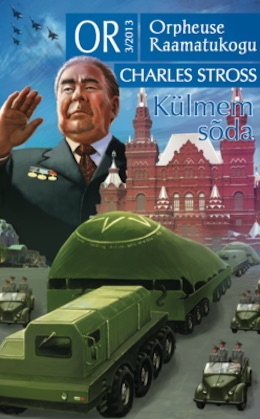

Today we’re looking at Charlie Stross’s alternate history novelette “A Colder War,” originally written c. 1997 and first published in Spectrum SF No. 3 in July 2000, Spoilers ahead.

“Once, when Roger was a young boy, his father took him to an open day at Nellis AFB, out in the California desert. Sunlight glared brilliantly from the polished silverplate flanks of the big bombers, sitting in their concrete-lined dispersal bays behind barriers and blinking radiation monitors. The brightly coloured streamers flying from their pitot tubes lent them a strange, almost festive appearance. But they were sleeping nightmares: once awakened, nobody—except the flight crew—could come within a mile of the nuclear-powered bombers and live.”

Summary

Roger Jourgensen, CIA analyst, has a tough assignment—to reduce complex intelligence to a digestible précis for the newly elected president (Reagan.) The Russians’ Project Koschei is “a sleeping giant pointed at NATO, more terrifying than any nuclear weapon.” Add in the Russians’ weaponized shoggoths, which have recently wiped out whole Afghan villages. By using them, Russia’s violated the Dresden Agreement of 1931, which even Hitler respected. That same agreement forbids mapping a certain central plateau of Antarctica, where the US has its own questionable projects underway. Jourgensen recalls his childhood dread of nuclear holocaust. Now he’d prefer he and his family perish in nuclear fire rather than face “what he suspects lurks out there, in the unexplored vastness beyond the gates.”

Jourgensen’s report goes well; he’s recruited by Colonel (Oliver) North to join his special team as CIA liaison. They work out of the Executive Office Building, with an executive order to use any means necessary to counter the use of, well, Outer weapons by US enemies.

One assignment takes him to Lake Vostok, deep beneath the Antarctic ice. America has appropriated a “gateway” shortcut between its bottom and ruins in Central Asia (Leng?). A minisubmarine transports high-grade Afghan heroin on this run, in which North takes an interest. The heroin, Jourgensen ascertains, came through fine. Not so the submariners, who show signs of extreme aging, probably due to a flare from the alien sun they’ve passed under. They later succumb to radiation poisoning, and missions through that gateway are suspended. North’s team does plant a radio telescope on the far side, in “XK Masada,” an ancient city on an alien world 600 light years closer to the galactic core than Earth. The air there’s too thin for humans, the sky’s indigo, the sun blood-red; symbols on the long-deserted buildings resemble those on the doors of a concrete bunker in the Ukraine, “behind which the subject of Project Koschei lies undead and sleeping: something evil, scraped from a nest in the drowned wreckage of a city on the Baltic floor.”

Professor (Stephen Jay) Gould visits North’s team to report on a creature he’s examined for them. It’s unmistakably Anomalocaris, an animal found among the rich Cambrian fossils of the Burgess Shale. Yet this specimen was recently dead, not even decomposed! More astonishingly, its tissues reveal it has no earthly relatives, not even in the archaeobacteria. In other words, it must be of alien origin. North concedes it was recovered through a gateway. Gould also opines that the so-called Predecessors—the barrel-bodied, star-headed beings uncovered by Miskatonic’s Antarctic expedition—were highly intelligent—indeed, he wonders whether humanity is worthy to inherit their technological crown.

Jourgensen remembers Nazi experiments on whether human brains could survive in proximity with the “Baltic Singularity,” now Russia’s Koschei. He supposes that Koschei’s “world-eating mind” dreams of feasting on fresh sapients, be they Predecessors or humans. Gould may be thrilled to confirm extraterrestrial life, but if he knew the whole truth, he wouldn’t be so happy.

Meeting with an Iranian informant, Jourgensen learns the Iraqis are stirring up cosmic trouble in Basra—the “unholy brotherhood of Takrit” sacrifice on the altar of “Yair-Suthot,” causing “fountains of blood” to spray in Tehran! Gates are opening everywhere! The situation is so desperate that Iran is willing to work even with Israel to develop nuclear defenses of its own against the “ancient abominations.”

Jourgensen ends up testifying before a Congressional committee about North’s activities. He admits that the “weakly godlike entity” at the heart of Project Koschei is “K-Thulu” and that the gateways connect to at least three other planets. At XK-Masada, the government’s prepared a retreat for selected members of humanity (you know, government people and their support staff)—it’s a city under a Buckminster Fuller-designed dome a mile high, defended by Patriot missiles and radar-invisible jets. The “bolt-hole” gate lies under the Executive Office Building, all ready for evacuation in event of war.

The committee’s interrupted by news of an attack. The military’s gone to Defcon One. Evacuation through the “bolt-hole” commences, and Jourgensen’s swept along. Later, at XK-Masada, North tells him how Saddam Hussein finally succeeded in stabilizing the gate into “Sothoth.” Mass destruction swept the Middle East. Iran panicked and went nuclear. Russia responded. Somehow the gates of the bunker in Ukraine opened, and Koschei was loosed. Now K-Thulu heads toward the Atlantic, and Jourgensen must help figure out what the US should do if it doesn’t stop there, because all their special weapon systems haven’t fazed it a bit.

Jourgensen complies, but horror and survivor’s guilt rack him. He often wanders outside Masada, surveying the dead landscape of a dying planet not even his own. He begins to converse with the void, which tells him in North’s voice that his family might still be alive. After all, there are fates worse than death. Within the “eater of souls” there’s eternal life. No one’s forgotten and allowed to rest in peace—instead they endlessly play out alternate endings to their lives in the soul-eater’s brain.

Roger considers suicide. But if his analysis of the situation is wrong, well, he’s still alive. If he’s right, death is no escape. Only why, he wonders, is hell so cold this time of year?

What’s Cyclopean: It’s the clinical, almost-but-not-quite random code phrases that stand out: GOLD JULY BOOJUM, SECRET INDIGO MARCH SNIPE, Project Koschei

The Degenerate Dutch: Cold War paranoia, Mythos-infused or otherwise, doesn’t make any of the powers involved look pretty.

Mythos Making: Per “Mountains of Madness,” this is what happens when blasphemously surviving nightmares squirm and splash out of their black lairs to newer and wider conquests.

Libronomicon: The Russians use tools described in the Kitab al Azif. “The Great Satan” doesn’t have quite the same referent here that it did in our universe.

Madness Takes Its Toll: The darkness between world’s broke Jimmy Carter’s faith and turned Lyndon B Johnson into an alcoholic. Then there’s the “world-eating mind adrift in brilliant dreams of madness, estivating in the absence of its prey.”

Ruthanna’s Commentary

I recall the ’90s as a precious, brief period between apocalypses. The Cold War had been peacefully, miraculously resolved. (Even if the Soviet Union’s collapse didn’t make the War’s eldritch weapons vanish, merely distribute them more widely.) Terrorism hadn’t yet provided a replacement existential enemy, and climate change didn’t loom large in the public consciousness. All we had to worry about was the hole in the ozone layer, war in the Middle East, austerity at home…

Into this optimistic gap came Charlie Stross with the proposition that Lovecraft was a very modern writer indeed. In his 2004 essay appending The Atrocity Archives, he opined that HPL perfectly presaged the fear of a manmade—and yet entirely inhuman—apocalypse. Seven years earlier, in “A Colder War,” he illustrates this idea in its primordial form. The Laundry books (of which TAA is the first) shade from nuclear paranoia into the civilization-breaking horrors of the 21st century. “Colder War” is darker and more focused—an ideal of the argument, unencumbered by any need to support later continuity.

This week’s story includes superficial precursors to the Laundry—the camera-esque guns, the Eater of Souls—but on a deeper level it reminds me of the many lifeless and dying alternate realities that the Laundry agents have encountered. Most of these worlds died through some variation on the events in “Colder War;” the latest book includes a delineation of all the CASE NIGHTMARE scenarios that constitute “solutions to the Fermi Paradox.” The eye of survival in the needle of extinction is very narrow indeed. In Stross’s universes, at least. In ours…?

We know about so many close calls. Not just the Cuban Missile Crisis, but bombs improperly secured, computer errors corrected at the last minute, blips disbelieved by one sensible soldier. Stanislav Petrov saved the world one day before I turned eight. In dozens of unconscionably irresponsible moments, we simply got lucky—Reagan’s “fifteen minutes” quip is an all-too-plausible jonbar point. With shoggot’im providing just a little extra impetus…

I grew up believing the bombs would fall any day. That experience is the sharpest generational divide I know. A friend, a decade younger, recently drove cross-country and camped cheerfully just outside the security zone of an ICBM silo. To me, that’s the rough equivalent of laying down your sleeping bag on the slab over Cthulhu’s bedroom. Stross’s metaphor seems exact.

In ’97, “A Colder War” was among my first exposures to Lovecraftian literature. On reread, it retains its power—it’s possibly the scariest Mythos story I’ve read. Having since read “At the Mountains of Madness” only enhances it. On this read, I’m also more familiar with the Drexlerian nanotech underlying Stross’s shoggoths, a clever reinterpretation of their amorphous power, and with the wondrous critters of the Burgess Shale. We’ve learned more about their place in evolution since the story was written, but I’m still totally open to Anomalocaris being extraterrestrial.

Speaking of Anomalocaris, the cameo by Steven Jay Gould provides a moment of pure delight in a deliciously dark story. I love his enthusiasm over the existence of alien life and the longevity of the Elder Thing artifacts. His inversion of Lovecraft’s terror-ridden deep time rants is pitch perfect. And in a context where terror would be fully appropriate, it induces every shiver Lovecraft could hope for.

Anne’s Commentary

This week’s story, which yes, unbelievably, I’ve just read for the first time, has roused me to new heights of geek bliss. How often do Stephen Jay Gould and Oliver North, Anomalocaris and K-Thulu, get to dance around each other in one story? Answer: If anyone can come up with another instance of this rare alignment of stars, let me know.

One of my favorite books is Gould’s 1989 Wonderful Life, a combined “biography” of the Burgess Shale, a taxonomic exploration of its Cambrian organisms, and some maybe-out-there evolutionary speculation. I heard Gould speak a couple times at Brown Bookstore and remember him as one of those uncommon people with so much enthusiasm for their subject that you couldn’t help basking in the energy. I can’t say I’m a fan of the other historical figures in the story: North, Fawn Hall (yeah, her hair really WAS that big), Reagan, Saddam Hussein, etc. However, they all played their alternate history parts here with gusto, on-page or off. And Anomalocaris! My favorite Burgess Shale creature, along with the also-mentioned Opabinia! I had a dream once that an Anomalocaris was floating around in my yard, which was both thrilling and terrifying. Hallucigenia, on the other hand, always struck me as improbable as a stand-alone beast. Though live specimens, waving their tentacle-thingies, would make nice hair ornaments (fin ornaments?) for Deep Ones. [RE: Maybe that’s why Hallucigenia is my favorite?]

The alternate history conceit of “A Colder War” is that Professor Dyer’s desperate attempt to stop Antarctic exploration (aka “At the Mountains of Madness”) did not succeed. In fact, it looks like he was right about the danger of his account, that it would only spur interest in that icy land of eternal death—or maybe eternal alien life. Nations rushed to mount expeditions, but by 1931 they’d discovered enough to sign off on the Dresden Agreement, which apparently forbade the development or use of alien technology as weapons. Even Hitler was supposed to have been spooked enough to respect the Agreement, except when he didn’t. We eventually learn that the Nazis were the ones to uncover the “Baltic Singularity”—a monstrous being “nested” in the ruins of a city drowned at the bottom of the sea. Nazi doctors investigated the Singularity’s capacity for inducing madness in humans. Looks like Mengele himself fell prey to its mind-warping emanations. But the Russians outdid the Nazis. If I’m reading this complex story right, they’re the ones who transported the Singularity from the Baltic to the Ukraine, where they tucked it into a giant concrete bunker to continue its long nap—until they unleashed it to wipe out the West, as US intelligence fears. This is the dreaded Koschei Project, and its subject is K-Thulu (we all know who THAT transliteration of the name refers to!)

But wait! Doesn’t Cthulhu lie dreaming in R’lyeh, under the South Pacific? What’s he doing in the Baltic? My mind races. Maybe the Japanese found a re-emerged R’lyeh and shipped its most famous denizen to their German allies? Only the ship sank in the Baltic. But wait, there’s already an ancient sunken city at the bottom of the Baltic! Okay, here’s a better theory. There’s more than one Cthulhu, so to speak. After all, it’s Lovecraft canon that Cthulhu is but the greatest of his Greater Race, its high priest. The Baltic Singularity could be another Cthulhuian (a lower-level priest?) whose city sank like R’lyeh at some point in cosmic time.

And then the “Baltic Singularity” brings to mind the “Baltic Anomaly,” a curious geological formation, or primordial artifact, or alien spaceship, discovered in 2011. So, yeah, Stross wrote his story around 1997, but maybe (cue new conspiracy theory) he had access to deep dark CIA documents detailing the Anomaly. You know, the photos that showed glyphs on the sunken city like those on the Project Koschei bunker! Uh oh.

Oh wait, I almost forgot the shoggoths, or shoggot’im as they’re probably more rightly called in their awful plurality or aggregate. The Russians have some, which they’ve somehow learned to control enough to use as weapons in Afghanistan. I guess they got them in Antarctica, from the “Predecessor” ruins. Or maybe from an under-ice lake like Kostok. Or maybe through a gateway to alien worlds. The possibilities!

There’s plenty of fun in “A Colder War,” like the wedding of Mythos and intelligence-military jargon, like North’s “febrile” hyperactivity and the Congressional hearing in which Jourgenson is grilled about the Russian shoggoth advantage. But Stross masterfully subordinates the lighter elements to a foreboding suspense and “cosmicophobic” anxiety that make the story genuinely chilling. Protagonist Jourgensen doesn’t even seem to experience the wonder that leavens many Lovecraft characters’ terror, in the face of proof that man is neither alone in sapience nor supreme master of creation. It’s Professor Gould who’s exhilarated by the vastly widened prospect of universe and life that Pabodie, Dyer and Atwood opened to the modern world.

Roger Jourgensen thinks Gould’s an idiot, that he couldn’t be happy if he knew the truth. The whole truth. The truth at which Roger later stares at XK-Masada: that he’s left one dying world for another dying world, and that even dying is no guarantee of peace. Not when there are devouring minds so infinitely curious as to subject assimilated psyches to endless revisions of their exits.

Which makes me think of Gould’s theory about rewinding and replaying evolutionary history! Whoa. Maybe K-Thulu is just experimenting with that idea, “weakly godlike agency” that he is.

Next week, a different war and a different Mythosian connection in Fritz Leiber’s “The Dreams of Albert Moreland.” (The link is a scan of the original fanzine. If you don’t enjoy squinting at 60-year-old typeset, you can also find the story in e-book format in The Second Fritz Leiber Megapack, among others.)

Ruthanna Emrys’s neo-Lovecraftian stories “The Litany of Earth” and “Those Who Watch” are available on Tor.com, along with the distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land” and “The Deepest Rift.” Winter Tide, a novel continuing Aphra Marsh’s story from “Litany,” will be available from the Tor.com imprint on April 4, 2017. Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Livejournal, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her first novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with the recently released sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.

If humans can smuggle drugs through gates, K-Thulu might also know a shortcut between different oceans.

I bloody love this story! I’m always trying to get people to read it. Well, along with Sun of Suns by Karl Schroeder.

“A Colder War” is Stross’s less-snarky-yet-more-scary take on the Mythos, building on the nuclear terror/cosmic horror conflations of Bruce Sterling’s “The Unthinkable”.

Open question for fans of Tim Powers: would you recommend Declare to someone who wasn’t particularly fond of Last Call?

This story is absolutely mind-blowing in its structure and content. Stross has a feel for describing bureaucratic spycraft that comes close to that of John le Carré, and that without having actually worked in the field. You can see some of the seeds of the Laundryverse, but it’s different enough to evoke entirely different feelings.

It has also stood the test of time, aging well, but this time around I found myself constantly pulling up memories of the whole Iran-Contra scandal in our timeline and trying to identify the various players. I could not for the life of me remember John Poindexter’s name until Stross gave it. And I’m still frustrated that I can’t identify any of the Congresscritters. I think I ought to be able to.

This story also puts a very different spin on the Israeli air strike on Iraq’s nuclear reactor, following an Iranian attack on the same facility. Basra was the site of some of the nastiest fighting in the Iran-Iraq war. The triggering incident here is probably Operation Badr, the Fourth Battle of Basra, which took place in mid to late March of 1986. It must have taken place a bit later or lasted a lot longer, since I’m assuming that K-Thulu broke free on April 26. Operation Koschei’s location in Ukraine must have been outside the city of Pripyat, near the town of Chornobyl.

@3 Schuyler: Yes, if you like the Laundry books, John le Carré, and/or are familiar with Kim Philby. Powers plays by tight rules; any historical personage is exactly where history says they were at the time in the story. Also Last Call is one of my least favorite Powers novels, pretty close to the bottom even, so it may not be indicative of your reaction to his larger body of work.

I like this story much more than the actual Laundry Files to be honest. Sadly, it is very rooted in a particular time so I wonder if current, young readers can get as much out of it.

I’ve read this story a few times, but only recently came across the theory (on TVtropes) that Jourgensen has already been devoured by the Eater of Souls and the entire story is him playing out an alternate ending to his life. Which would make the voice he hears at the end K-THULU taunting him.

Speaking of K-THULU, I assumed that R’lyeh could be accessed from multiple points on Earth due to its wibbly-wobbly non-Euclidean geometry-wometry; it likely exists only partly in our familiar three-dimensional space.

Also, did anyone else get the impression that the XK-PLUTO bombers were piloted by brains in Mi-Go cylinders?

I have to say that this is probably my absolute favorite non-Lovecraft story set in the Lovecraft mythopoeia. It’s bleak as hell and yet it creates a world that could sustain an ongoing series — think Stargate: SG-1 meets Delta Green. Simply disregard everything after the section titled “The Great Satan” and go from there. No bombing, K-THULU stays in his box, the gate to Sothoth stays shut. The Cold War winds down, the Berlin Wall crumbles along with the USSR, the Shoggot’im end up on the black market, Saddam invades Kuwait, NATO siezes the Sothoth gate during Desert Storm, the Twin Towers collapse, the War on Terror is a pretense to round up cultists and oust Saddam before he can retake the Sothoth gate, and the 2016 election is between an avatar of the King in Yellow and a Mi-Go in a human suit. Meanwhile we’ve had NASA exploring the gates in search of alien relics that can protect us from Project Koschei and other godlike entities.

@@.-@:

The congressman who does most of the talking in the hearings reminded me of Sam Erwin, from the Watergate hearings. Don’t know if he was still active in the Reagan years.

@7: Sam Ervin died in 1985. Looking, both the Tower Commission and the Congressional investigation came after the situation here would have blown up completely. Tower in very late 86, the Congressional hearings the following year. I suppose John Tower is a possibility. The chairs of the Congressional investigation were Lee Hamilton and Daniel Inouye. I don’t know anything about Hamilton, but none of the people questioning Jourgensen bear any similarity to Inouye.

I love this story, and recently re-read it for the first time in several years. Ruthanna and Anne’s take on it will make me do so again soon.

I worked in Washington, DC for a few years in the 80s, and attended several briefings and events in the Old Executive Office Building. If only I had known about the gate in the basement!

SchuylerH @3: Yes, I would. I like both of those books a lot but I think it’s safe to say they’re pretty different in style and scope.

vinsentient @5: I’m a compulsive reader of the Laundry series but I’m still not sure if I *like* them, or just the idea of them. Stross in novel mode tends to repeat himself a lot (not just from one book to the next – IIRC he’s more than once duplicated virtually the same infodump or character epiphany twice within the same book); this one, like the shorter Laundry pieces, feels like a better length. Plus his sense of humor in the Laundry books is incredibly grating to me – or I should say, the jokes: he does some subtler humor based on characterization and social situations that I like a lot, but whenever the narrator is embellishing every sentence with jokey roundabout references to every thing or event, or consistently calling his iPhone a “JesusPhone”, I just wish someone else were writing it (I know the narrator is arguably supposed to be annoying, but that doesn’t help; having a lot of computer background myself like Stross also doesn’t help, it just makes me feel like I’m trapped with one of my most garrulous former co-workers)

My friend drew the cover displayed on top. How cool is that? :D

@8

A more detailed rundown than I’d thought to do – thanks – the last time I paid attention to this sort of thing was during the Watergate hearings. I’d forgotten about the Iran-Contra hearings, although I should have remembered – was living in the US at the time. At least we can probably agree that it was unlikely to be Ken Starr.

@11

Pretty damn cool.

Having just complained about the Laundry books— they do have lots of ideas that I really love. Some are just the kind of geeky “wouldn’t it be cool if fantasy concept X really worked like Y” thing that appeals to me on a techie/fanfic level, like the general premise of magic being a side effect of math and computation, but then Stross sometimes takes them to a meatier thematic level. For instance, the ultimate doom of Earth isn’t just going to be triggered by a cosmic “stars coming into alignment” event, as Lovecraft sometimes alludes to; nor is it necessarily due to evil people doing occult things on purpose, as it is in other Lovecraft stories and in “A Colder War”. Instead, although the Laundry heroes still have to stop the evil people, the whole human race is also directly speeding up the apocalypse just by existing— because the number of conscious people keeps increasing, and consciousness itself creates a dangerous magical pressure. The doom is sort of personal and impersonal at the same time, which I think ties in well with the kind of post-Cold-War shift in apocalyptic fears that Ruthanna mentioned. And while “A Colder War” gives us a worst-case scenario where governments are doing the most reckless things possible, in the Laundry world most of the authorities are actually pretty competent, but that won’t necessarily make much difference… which is scarier.

Sorry to comment so much, but since no one mentioned this: Project Koschei is named after a Russian mythic figure who’s sort of an all-purpose evil wizard, often called “the Deathless”. I don’t know if Stross gave much thought to this beyond “what’s a Russian name related to immortal evil”, but it is kind of a weird thing to combine with Lovecraftian mythos, because like most folk-tale characters Koschei tends to be a very personal antagonist in spite of his great powers. That is, he’s more likely to kidnap you because you are a young woman he’s lusting after— or try to magically kill you because that young woman is your girlfriend or sister— than to conquer or destroy your world or even your town. Many SF/fantasy writers have made use of Koschei but mostly in this smaller-scale aspect, although for instance Catherynne Valente’s novel Deathless gives him a more cosmic archetypal role.

It may be that this is a very subtle intentional joke: that is, the Soviets have misinterpreted Cthulhu as something more anthropomorphic that one could maybe ally with or bargain with, because that idea is so deeply baked into their cultural history, and therefore their project was doomed to go wrong (I mean, even more doomed than every other “try to somehow control a huge monster” project).

@6. “the 2016 election is between an avatar of the King in Yellow and a Mi-Go in a human suit.”

Are we entirely sure it isn’t?

DemetriosX @@.-@: Regarding spycraft and bureaucracy— Stross is a big fan of Len Deighton and has cited him as the main influence on his own spy stuff. I haven’t read Deighton, but Stross’s praise of him makes me want to.

@14:

Koschei is also the name of the demiurge who created the Universe in Cabell’s Poictesme novels. Mind you, Cabell pulls in names from all of the world’s mythologies in his books, it seems, and the name given to a particular character may or may not bear some relationship to their attributes – Manuel the Redeemer fits his name, for instance (at least as history records his life, not as he actually lived it), but Koschei? Totally disenchanted, as I recall, but I don’t see what that has to do with the nature of the Slavic Koschei.

@10 – yes, on Stross’ sense of humor. I work with people like that. I don’t like their sense of humor and I don’t like his. Its cringe-inducing. I see it as a sign of realism, however – the people in the Laundry would be like that, sadly.

A surefire way to make a story terrify me — add nuclear weapons. It’s a large part of why the Horsepersons give me recurring nightmares, while most Lovecraftian things* don’t. So I’m nope-ing out of this one. Props to him for involving obscure Paleontologic probably-invertebrates, though.

*Not counting the election, which has provoked me to frequent usage of the Lovecraft Insult Generator.

DOuthier @@@@@ 6: Re XK-PLUTO bombers and Mi-Go. When you put it like that, it’s obvious, isn’t it? Never caught that before!

Gerry O’brien @@@@@ 9: I work in DC now, and have been there a couple of times as well. So far the most interesting thing I’ve seen in the basement is the bowling alley, but then one isn’t advised to go randomly poking around unauthorized areas of federal buildings. But Stross’s version is obviously an alternate reality–what other reason could there be for having a Congressional hearing in the Executive Office Building? That, and at least according to the tour guide the swimming pool in question is buried under the White House press room…

Celebrinnen @@@@@ 11: That’s awesome. It’s an excellent cover!

AeronaGreenjoy @@@@@ 9: You saw, yes, that Cthulhu endorsed Trump? And then, in September, appeared to change His mind.

I’ll have to read this one too.

If you like the Opabinia and the other wtf-inducing eurypterids of the cambrian era, have a look at the Tully Monster.

@@.-@ & 10: Thank you. I have a recurring problem of starting to read an author’s works with precisely the wrong book. (Some day, when the stars are right, I will tell the story of the several attempts I needed to get into Ramsey Campbell’s fiction.)

@11: Very.

@16: It’s amusing that Deighton should come up; he seems to be getting some mainstream promotion again ahead of the release of the adaptation of his alternate history novel SS-GB.

Re Koschei: I don’t think this is supposed to be the Russian’s name for what’s going on, but rather the American intelligence designation. It seems to me from the spelling K-Thulu and the congressman/senator’s reaction to it that the K designation is used for “weakly godlike entities”. So the CIA probably just went looking for an appropriate K-word to label whatever the Russians were doing in Ukraine.

I’m too young to have much idea of Iran-Contra (too young to notice it at the time, but not young enough that it was taught as history), so I missed many of those allusions. However, I am just old enough to remember the Cold War, and the constant knowledge that I could be three minutes from dead at any time. That feeling of imminent, but impersonal doom, is my touchstone for existential dread.

A Colder War is still one of the stories that scares me the most.

@15: can’t opine on the King, but the Mi-go are actually pretty good at computer security: you have a bunch of grumpy brains hooked up to cybernetics, you don’t want them to get any ideas.

The story was published in 2000: not sure where that 1997 date comes from, since it apparently was prompted by a thread on the old google alternate history group in 1999, which Stross said himself in 2000, here:

I have a novella in the current issue of Spectrum SF that sort of spun

off of one of the Lovecraft threads (shades of “what if ‘At the Mountains

of Madness’ had actually been for real?”). Should be in the specialist SF

bookshops in the UK (and via http://www.spectrumpublishing.com) in a week or two.

Think “Dr Strangelove meets Cthulhu” ...

— Charlie

The original thread is here.

@25: He said here that he started writing or at least thinking about this story in 1997, while the Laundryverse started to ferment in 98/99.

@20: That endorsement is well-reasoned. But endorsing anyone who strives to facilitate marine pollution, e.g. through fossil fuel extraction and usage, is a dastardly betrayal of the Deep Ones.

The sorry functionary Roger feels uncomfortably close to home. With its mixture of Big Old Menace and small human folly, this story unsettles me more than most of Lovecraft’s original tales (apart from the “Color”, which seriously rattled me). It’s still free online at Infinity Plus.

@6: Good thought about XK-PLUTO. There was a definite hint in Roger’s meditations that the bombers had something more to them than the film voiceovers described. Better not speculate, maybe, on the nature of MK-NIGHTMARE…

@20 &28: The clues are all there — the flight crew’s immunity to radiation, the jets’ ability to remain airborne for months at a time without landing to swap out pilots, even the codename. XK appears to designate alien origin, while PLUTO is likely a reference to both the plutonium in the plane’s reactor and payload as well as the origin of its technology. Yet Stross merely implies all this rather than state it outright; one of the reasons A Colder War is such a masterful tale is the deftness with which its worldbuilding is accomplished. Minimal infodumps, lots and lots of implication

And with implication comes interpretation. Anything not stated outright is subject to multiple readings. Is Jourgensen going crazy or hearing an actual voice? If it’s a real voice, then whose? Nyarlathotep’s? Or is it the Eater of Souls taunting him with knowledge of his own fate, making the entire story an alternate ending to what *really* happened? If that’s the case, then what *did* really happen? Is K-THULU really awake and ravening with delight, or did it perhaps awake only briefly, eat Jourgensen and a few others, and go back to sleep, as in The Call of Cthulhu? Hell, is K-THULU really the same entity as the Eater of Souls at all? We have only the voice’s word on that.

Hell, it’s possible that Jourgensen really is on MK-MASADA but that the reports he got are false. Maybe there was a purge of certain “undesirable elements” in the Reagan administration via exile to an alien planet under false pretenses.

There’s no way to know.

@29 DOuthier dammit now I have to find room in the reading schedule for yet another pass of A Colder War!

SchuylerH @22: Has Campbell really not been covered in this series yet? If not, I’m sure they’ll get to him before long and then the stars will be right. He might show up to talk back too, I know he’s commented on this site before.

Going out on a limb and guessing the ‘cauliflower’ thing in Gould’s presentation was a Moravec Bush Robot – probably less efficient than a well-programmed Shoggoth, but perhaps less trouble when rebellious.

Bruce Munroe @@@@@ 25: Thanks for the catch. You’re right that it’s 2000; I misread the “written in” date as the publication date. I don’t think that substantially changes my temporal analysis at least–the brief shining (if slightly tarnished) period between the Cold War and the War on Terror provides a particular perspective.

Eli Bishop @@@@@ 31: Yes, we’ll get to Campbell one of these weeks.

@3 Schuyler… count me in with the Powers’ fans who recommend this novel. If you love tales of seekers of knowledge poking around forbidden cities in the Empty Quarter, and accounts of desperate searches for means with which to kill Eldritch Entities, then Declare should be right up your alley.

In my estimation, A Colder War seems less dated than the ‘Laundry’ novels, even though it’s firmly rooted in one particular decade. While I love the Laundry, the inclusion of so many snarky internet-culture references interferes a bit with the ‘suspension of disbelief’. Stross really pulls of ACW beautifully, by which I mean horrifically.

I love all of the inferences made about the story- the bit about the Yuggoth-brain cylinder-piloted planes is brilliant. Obviously, the Russians have counterparts… putting the MiG in Mi-Go.

I just realized there’s no link to the story from the original discussion piece. So if you want to read A Colder War, that’s a totally legit site where it’s available for free.

Am having a fascinating pass-the-popcorn time reading the comments. I figure we’re far enough in now that if you want to ask me anything, I’ll try to answer.

(NB: I hadn’t read anything about the Mi-Go when I wrote ACW. Which I started in 1993, then shelved until 1997, when I finished and sold it to Spectrum SF.)

(NB: I hadn’t read anything about the Mi-Go when I wrote ACW. Which I started in 1993, then shelved until 1997, when I finished and sold it to Spectrum SF.)

The Yithians used their psionic hardware to suppress those memories…

DOuthier @@@@@ 29 et al.:

“XK-PLUTO” is, I’m pretty sure, a reference to Project Pluto, which was a real-world US exploratory attempt to design a nuclear-powered ramjet engine for a long-duration cruise missile/unmanned bomber. (“Since nuclear power gave it almost unlimited range, the missile could cruise in circles over the ocean until ordered ‘down to the deck’ for its supersonic dash to targets in the Soviet Union. The SLAM as proposed would carry a payload of many nuclear weapons to be dropped on multiple targets, making the cruise missile into an unmanned bomber.”)

Charlie’s imagining a world where they went ahead and developed it as a manned bomber (the flight crew are the only ones who can survive because they’re always in front of the radioactive exhaust, plus probably they’ve got some shielding). Rather then being a Dresden-Agreement-violating implementation of alien technology, I think the idea works just as well as an example of how insane purely human thinking and technology could get during the Cold War.

Peter Erwin @37: not quite.

Project PLUTO (the real one) had a couple of extra stings in the tail; firstly, flying at Mach 3 at treetop height, its sonic boom would break buildings and kill people under its flight path, and secondly, after dropping all it’s H-bombs it would fly in circles over hostile territory until its plutonium-fuelled ramjet reactor melted down, spewing fallout everywhere — in other words, every part of the weapons system was lethally deadly!

XK-PLUTO … firstly, the two-letter prefix followed by codeword thing was used by the US military and CIA in the post-WW2 period (there’s an apocryphal story about a senator at a CIA briefing on the Middle East in the late 60s who asked, “what exactly is this project KU-Wait all about?”), and secondly, it’s based on the plans for the manned subsonic nuclear-powered bomber that was cancelled by JFK in 1962; a test bed aircraft, the NB-36, actually flew with a critical nuclear reactor aboard, and the air-cooled dual-turbine nuclear-heated propulsion unit was ground-tested (but a true nuclear-propelled airframe was never built). This story speculatively had a monstrous nuclear powered B-36 descended strategic bomber as part of the deterrent triad. (In reality, the nuclear bomber program was rendered obsolete by first, in-flight refueling, and second, the ICBM.)

@17: And Cabell’s use of Koschei led to Heinlein’s later use of the same name.

A colder war is an excellent story and much more depressing than one first realises. Which in my view is double plus good.

“Nellis AFB, out in the California desert”

Nellis is just outside Las Vegas, in Nevada. Edwards AFB is in the California desert.

@19 Anomalocaris, Opabinia and Hallucigenia were real creatures, if that’s what you meant.